As individuals and producers of creative content, be it in visual or textual formats, we can choose to be either hapless victims or active participants shaping this inevitable tide of events. -

relationship between blogging and journalism, the big question now is not as much as how blogging has threatened journalism, but how journalists can tap on the opportunities now made visible and available by bloggers.

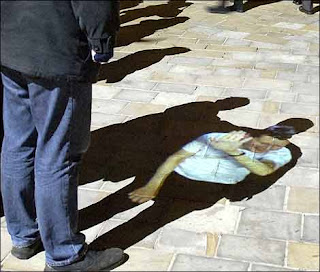

Videoplace is an early example of augmented reality art, done by an artist whose interests lay mostly in VR. The installation features computer projection that interacts with the viewer's physical shadow.

Videoplace is an early example of augmented reality art, done by an artist whose interests lay mostly in VR. The installation features computer projection that interacts with the viewer's physical shadow. Myron Krueger is one of the original pioneers of virtual reality and interactive art. Beginning in 1969, Krueger developed the prototypes for what would eventually be called Virtual Reality. These "responsive environments" responded to the movement and gesture of the viewer through an elaborate system of sensing floors, graphic tables, and video cameras. Audience members could directly interact with the video projections of others interacted with a shared environment. Krueger also pioneered the development of unencumbered, full-body participation in computer-created telecommunication experiences and coined the term "Artificial Reality" in 1973 to describe the ultimate expression of this concept. [Jeremy Turner of CTheory]

After several other experiments, VIDEOPLACE was created where the computer had control over the relationship between the participant's image and the objects in the graphic scene. It could coordinate the movement of a graphic object with the actions of the participant. While gravity affects the physical body, it may not control or confine the image which could float, if needed. A series of simulations could be programmed based on any action and Videoplace offered over 50 compositions and interactions (including Critter, Individual Medley, Fractal, Finger Painting, Digital Drawing, Body Surfacing, Replay, among others). To illustrate, when the participant's silhouette pushed a graphic object-the computer could choose to move the object or the silhouette. Or, as in Finger Painting where each finger created flowing paint without the distraction of the silhouette.

The definition of ‹art beyond art› amounts to a negation of an understanding of art that is based on accumulative and historically linear findings. Interest focuses no longer on the autonomy of a work of art, a subject much discussed during modernism (and already wholly assimilated into contemporary art), but on art’s emancipation from art itself. This shift implies that the modernist tendency to take issue with the arguments of a discourse within the discourse itself has been overcome. It also signifies the demand for a ‹reconstruction of the area› on new foundations which place in question several of its basic theoretical generalizations and many of its methods.

The argument of the essays can be summarized as follows: explanations delivered by art are constitutively neither reductionist nor transcendental; the function of art consists in expanding realities, knowledge and experiences; this process can take its course dialogically or consensually (through seduction), or by means of canonization (through control or coercion). Further paradigm shifts specifically relevant to media art will be examined below.

Media art—in its diverse forms ranging from audiovisual installations to interactive systems, from hypermedia to artificial reality, from the net to cyberspace—reinforces the idea of ‹interdisciplinarity,› which reaches much further than the aforementioned considerations about the relationship of art and technology. In the context of interdisciplinarity, the intermeshing of art, technologies, and science refers to the process that brings about convergence, interference, appropriation, overlapping and interpenetration; a process successively leading to the generation of referential networks and reciprocal— non-hierarchic—influences.

After the exodus of art from conventional presentation spaces such as museums or galleries and the conquest of public places, streets, towns, landscapes (e.g. Land Art, Performance, Happening), the fact that spatiotemporal expansion and the wider use of

materials arrived at a deeper significance of ubiquity (the possibility of being present at all place at once or simultaneously), dematerialization (independence of the physical-material existence of the object) and participation (the use of interactive network resources) is without doubt brought about by the deployment of so-called new media—such as the telecommunications system.

All of the telecommunications projects developed from the 1970s onward, such as those of satellite art, were basically attempts to transform the medium into a meta-medium permitting art spatial and temporal ubiquity. That was what gave Nam June Paik, for example, the idea that a work could be created in several different places at once, as outlined in the score in 1961. Paik’s efforts to accomplish meta-communication led to his most important contributions to satellite art, such as in 1977 «Nine Minutes Live,» his direct satellite telecast of performances in Europe and the USA for the opening of the Documenta 6 in Kassel, and in 1984 «Good Morning Mr. Orwell,» organized jointly by the Centre Pompidou and the broadcaster WNET-TV, with whichPaik succeeded in realizing a live satellite program that was participative as well as simultaneous. According to Paik, satellite art was destined to become the most important non-material work in post-industrial society.

The formation of international projects in the 1970s was a crucial stimulus for art in conjunction with telecommunication as well as for the notion of ubiquity. The Brazilian Waldemar Cordeiro,a pioneer of Computer Art, in 1971 identified the inadequacy of communications media as a form of information transmission and the inefficiency of information as language, thought, and action as being the causes of the crisis of contemporary art. Cordeiro asserted in his Manifest Arteônica that art whose main emphasis lies on the material object restricts audience access to the work and therefore meets the cultural standards of modern society neither qualitatively nor quantitatively. Cordeiro’s deliberations in regard to global networking and free, telecommunication-enabled audience access to a work of art anticipated the notion of ubiquity, participation, and net art.

Francesca Woodman's photography had a strong impact on me when I first started taking photography seriously; her work along with others (Man Ray, Duane Michel’s, Ralph Meatyard, Moholy-nagy, Jerry Uelsmann, and Dali) definitely inspired me to experiment with movement, blurring, and manipulation within the medium. Woodman blurs fantasy with reality in a way which has always inspired me to find the unusual in everyday life. I want to create scenes for the audience to be a part of; something which the viewer knows must exist but has the same unusual eerie feel of standing in a dark room looking at an installation piece.

Francesca Woodman's photography had a strong impact on me when I first started taking photography seriously; her work along with others (Man Ray, Duane Michel’s, Ralph Meatyard, Moholy-nagy, Jerry Uelsmann, and Dali) definitely inspired me to experiment with movement, blurring, and manipulation within the medium. Woodman blurs fantasy with reality in a way which has always inspired me to find the unusual in everyday life. I want to create scenes for the audience to be a part of; something which the viewer knows must exist but has the same unusual eerie feel of standing in a dark room looking at an installation piece.

The categorical imperative is the central philosophical concept of the moral philosophy of Immanuel Kant, and of modern deontological ethics. Kant introduced this concept in Groundwork of the Metaphysic of Morals. Here, the categorical imperative is outlined according to the arguments found in his work.

Kant thought that human beings occupy a special place in creation and that morality can be summed up in one, ultimate commandment of reason, or imperative, from which all duties and obligations derive. He defined an imperative as any proposition that declares a certain action (or inaction) to be necessary. A hypothetical imperative would compel action in a given circumstance: If I wish to satisfy my thirst, then I must drink something. A categorical imperative would denote an absolute, unconditional requirement that exerts its authority in all circumstances, both required and justified as an end in itself. It is best known in its first formulation:

"Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law."

He expressed extreme dissatisfaction with the moral philosophy of his day because he believed it could never surpass the level of hypothetical imperatives. For example, a utilitarian would say that murder is wrong because it does not maximize good for the greatest number of people; but this would be irrelevant to someone who is concerned only with maximizing the positive outcome for themselves. Consequently, Kant argued, hypothetical moral systems cannot persuade moral action or be regarded as bases for moral judgments against others, because the imperatives they are based on rely too heavily on subjective considerations. A deontological moral system based on the demands of the categorical imperative was presented as an alternative.

Plato: The Allegory of the Cave, from The Republic

Whereas our argument shows that the power and capacity of learning exists in the soul already; and that just as the eye was unable to turn from darkness to light without the whole body, so too the instrument of knowledge can only by the movement of the whole soul be turned from the world of becoming into that of being, and learn by degrees to endure the sight of being and of the brightest and best of being, or in other words, of the good.

*The 1984 film Once Upon a Time in America, where it is occasionally seen in the Opium house.