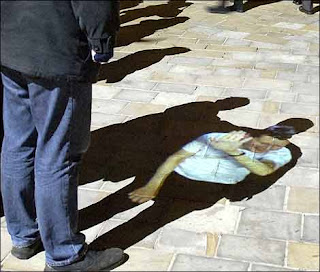

-the shadow work of Lozano-Hemmer has greatly influenced the progression of my project, I love the way he actively challenges the audience to participate with art in a public space, which is something I would like to explore in my final work. I want to create an interactive installation.

A spectacle of light and shadow transformed part of the waterfront as Wellington plays host to one the world's largest interactive artworks. Unveiled for the duration of the NZ International Arts Festival outside Te Papa on Cable Street, from 22 February until 16 March 2008.

Transforming a space of around 1,000 square metres, Body Movies is a free public art installation featuring 1,000 photo portraits of people taken on the streets in and around Wellington, as well as using a bank of photographs from Rotterdam and Hong Kong. As darkness falls the photo images will be cast by a powerful projector onto the side of Te Papa and then completely washed out by white bright light from 10,000-watt lamps placed at ground level. As soon as people walk in the area, their shadows are projected and the photo portraits are revealed within them in a variety of scenes. People can match, animate or embody a portrait by walking around and changing the scale of their shadow engaging “in a game of mimicry and representation” says the artist, Rafael Lozano-Hemmer.

A fusion of technology and public art, Body Movies is the brainchild of award- winning Mexican-Canadian artist, Rafael Lozano-Hemmer that he describes as a relational architectural installation. It is inspired by Samuel van Hoogstraten’s 1675 engraving The Shadow Dance. Lozano-Hemmer has employed the same image distortion effect, and updated it with 21st-century technology, actively challenging the community to participate with art in a public space. “Every time we show this piece, the behaviours are totally different, ranging from playful parading to erotic performances to aggressive stances. On average, about half the participants try to match the portraits by enlarging or reducing their shadows, while the other half is more interested in playing with each other's shadow,” says Lozano-Hemmer, who won the Prix Ars Electronica Award for Distinction in Interactive Art for this work. “In Rotterdam, where the work premiered, participants started using props after a few days. Breakdancers appeared. People brought their pets. A man in a wheelchair projected his shadow 22 metres high and he seemed to derive a lot of pleasure from crushing everybody around him.” A camera-based tracking system monitors the placement of the shadows, and when all shadows match the location of the portraits in a given scene, the controlled computer changes the scene to a new set of portraits. A small .wav sound is heard to give feedback to the people in the space when they have matched the portrait.

Spencer Finch

-Darkness and light. Blindness and insight. Nature and Science. These are the dichotomies described by Charles LaBelle which arise in Finch’s work. His work is inspiring for me because of these, I am interested in creating some kind of balance within the technology I wish to use in my installation.

Sensing that our observations must be tied to experience if we are to get at the truth of something, Finch is compelled continually to expand the scope of his projects, returning to the same sites at all hours to look again and again. He traveled to Rouen to visit the cathedral painted by Claude Monet but found the building closed for renovation. Undeterred, Finch decided to make a series of paintings depicting the colors of various objects in his hotel room. By the time he had completed the arduous task of matching 55 colors, the changing light had altered every one. Thus the work grew into a triptych, a wry blend of Conceptual and Impressionist methodologies, representing the same set of colors in the morning, afternoon, and evening. As Finch is fascinated with the interaction of the physiological and the psychological aspects of perception, the way our inner world casts a veil over the outer, it makes sense that he would travel thousands of miles to make a work that explored the tiniest details of his hotel room. For him vision is an act of projection as much as of apprehension. . . . Darkness and light. Blindness and insight. Nature and Science. These dichotomies arise in Finch’s work only to have their usefulness and validity interrogated. Their too-easy formulas and their promise of an absolute veracity are not to be trusted.

His work for the past decade had consciously distilled these issues and has grown richer, more potent. Resisting conclusion, Finch nevertheless aspires to a greater appreciation of the problem. . . excerpt from Charles LaBelle, Frieze pp. 66-69, May 2003 This means that Finch’s understanding of color theory, in the end, doesn’t amount to an alternative to formalism or Conceptualism. He is unafraid to inhabit the paradox that art exists in the play between language and perception. What many artists and theorists find unbearable, literally, the ‘speaking against itself’ implied in para-doxa, is for Finch less something to escape than the very condition necessary for his art practice. That is why his work demonstrates a Proustian interest in the difficulties and disappointments of recollection. He knows that color lies at the boundary of what we see and what we remember. Despite the thick red line of humor that runs through his work, Finch’s projects are always laced with the acute pathos of someone disappointed by both

perception and language and by their mutual exclusivity and incompatibility. "There is always a paradox inherent in vision, an impossible desire to see yourself seeing. A lot of my work probes this tension; to want to see, but not being able to,” Finch says in a catalogue for a 1997 show at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, CT. Color is less a trope of indeterminacy than a way to

re-create an almost visceral experience of our impossible desire to name our perceptions.

No comments:

Post a Comment